You Need A Kitchen Slide Rule

Kitchen work is all about proportions: sometimes the recipe is for four servings but you need six; maybe the recipe calls for 80 g of butter but you only have 57 g, so you have to adjust the other ingredients to match.

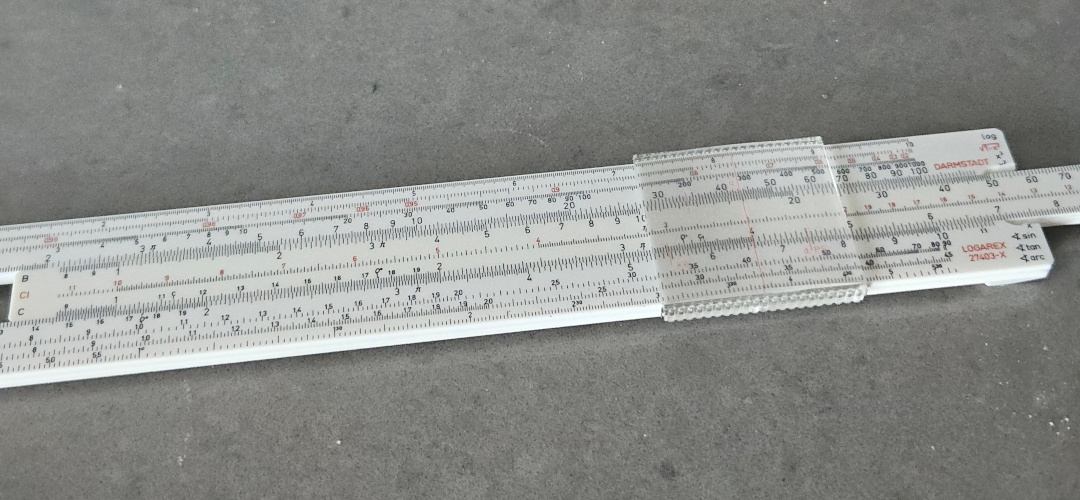

We could use an electronic calculator to figure out the rescaled amounts, but a slide rule makes it so much easier. The picture above was taken while following a recipe that called for 2 tsp of baking powder, and I wanted to make as large a batch as I could given the remaining 3.3 tsp of baking powder I had – a proportion of 2:3.3. You can see the slide rule is set to a proportion of 2:3.3 because – if you open the image in a new tab to make it larger – the number 2 on the C scale (on the bottom of the sliding middle part) is above 3.3 on the D scale just below.

But wait, the number 1 on the C scale is also just above 1.65 on the D scale. And 14 (or, if you will, 1.4, since with slide rules we ignore decimal points) on the C scale is above 23.1 on the D scale. Indeed. It’s set to those proportions too, because they are the same proportion. This is what makes the slide rule so powerful.

Once the slide rule is set to the constraining proportion, in this case 2:3.3, we can instantly read off all other amounts from it with no additional manipulation. If the recipe calls for three cups of flour, we’ll find 3 on the C scale and look what’s below it on the D scale: seems like we need 4.95 cups of flour. The recipe says 25 g of butter: we’ll take what’s under 25 on the C scale, i.e. 41.25 g. Having set the slide rule once, it then serves as a custom scaling table for the rest of the recipe.

This article spread beyond my usual audience! This is not so much about cooking as it is about having fun with maths in an almost useful way. Even if you disagree about how useful it is, you might have learned something new. If so, you should subscribe to receive weekly summaries of new articles by email. If you don't like it, you can unsubscribe any time.

Kitchen work is all about proportions, and nothing beats the slide rule for proportions. The reason I write this article is I just found myself in someone else’s kitchen and they didn’t have a slide rule. Only then did I realise how much I take my kitchen slide rule for granted.

Bakers understand the importance of proportions in cooking; they even write their recipes normalised to the weight of flour, meaning all other ingredients are given in proportion to the amount of flour. This makes it easier to compare recipes, too, because when they are normalised to the weight of a common ingredient, it is easier to see which recipe is sweeter, saltier, umamier, etc.

We can use the slide rule to scale recipes while cooking, but we can also use it when learning to cook something new, by taking a hint from the bakers. We look at multiple recipes and – using the slide rule – write up a table with the relative proportions of each ingredient in each recipe. This lets us see which ingredient amounts must be precise (they vary little between recipes) and which are added mainly to taste (they vary more between recipes.) Here’s an example for regular basil pesto1 Normalised to the amount of oil, because it’s (a) an important ingredient, and (b) likely to be somewhat reliably measured by everyone, in contrast to e.g. “a cup of basil leaves” which could really mean very many different amounts of basil.:

| Ingredient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olive oil (cups) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Pine nuts (cups) | 1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Basil (cups) | 4 | 2 | 0.6 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Parmesan (cups) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| Garlic (cloves) | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4.5 | 2 | 2 |

| Lemon (tbsp) | 4 | − | − | 0.5 | 1 | 3 |

Although the coefficient of variation is quite high for all ingredients, it seems that pine nuts, basil leaves, garlic, and lemon juice are all added to taste, whereas the parmesan is important for the structure of the pesto.

Everyone should have a slide rule in their kitchen drawers. I’m honestly surprised it is not standard equipment. Once set up, it’s a mess-free, multitasking-friendly way to achieve instant calculations with almost no work.