Paper Airplanes: Aerodynamics And Stability

When I was young I loved experimenting with paper airplanes. I like to pretend that those early days of trial and error was my introduction to science, but honestly I did not work systematically enough for it to even pretend to be science.1 I tweaked something, performed one test flight, and if that flight by accident was more successful than the previous one I recorded the tweak as a success, otherwise as a failure. In other words, what got recorded as an improvement and not was mainly down to luck.

My son is now at an age where he understands how to throw paper airplanes, but is not yet able to fold them, which means I get the fun of folding different designs for him. Since I’m also more scientifically literate, I can now also find real improvements by reasoning from general principles and systematic experimentation.2 One needs to compare across multiple test flights in order to determine how big the effect size of the adjustment is compared to the role of luck. That’s one of the pillars of science: ruling out the effect of luck. (The other pillar is replication effort; science works because it constantly tries do destroy itself.)

This article documents some of my early discoveries in this process, and – more importantly – areas of further inquisition where I don’t yet know the answer.

Nobody knows anything about paper airplanes

It seems like everyone approaches paper airplane design mainly through trial and error. When looking up designs, it’s only

I did this and it was great!

and never

These aspects of the design contribute this way, and if you want to make such-and-such adjustment, you may have to compensate this-or-that way.

Nobody sharing paper airplane designs seem to know what they are talking about! This is a little disappointing to me, because everyone knows how to fold paper airplanes. It should be a rich field of study! Maybe I just haven’t found the right community.

What knowledge is available about the principles of paper airplane design? There’s a strong overlap with real airplane design, but it is not a perfect match.

First, let’s focus on stability

I wanted to write an article covering both stability and performance of paper airplanes, but it turns out I know way too little to make a dent on performance. For that reason, I will focus on stability for now, and we’ll discuss performance later.3 If I get around to it, which is the everliving disclaimer on this site.

So, in this article we will not be making any designs from scratch. This article assumes we have folded a paper airplane, and now we want to know why the hell it doesn’t fly properly.

Two surfaces, three forces

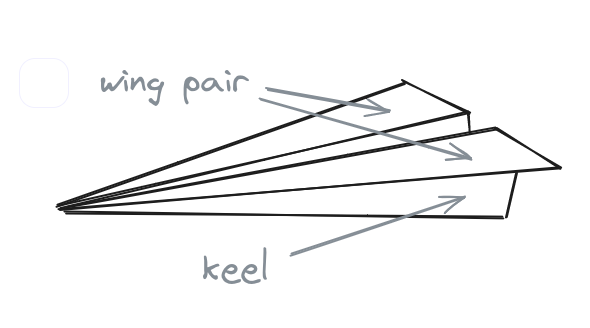

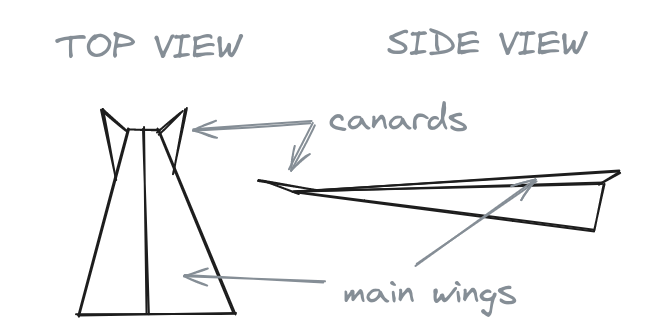

In some sense, it should be easy. Paper airplanes often have only two different aerodynamic surfaces: the wing pair and the keel.4 Some designs have canards, which are important aerodynamic surfaces, but the ones that don’t often have wings shaped such that the front part of the main wing acts as a canard. So we can treat the canard-wearing relatives sort of like they have just the one wing pair.

Figure 1: Paper airplane anatomy

Technical note: this article has illustrations which contain black outlines on a transparent background. If you use some css hack that changes backgrounds to a dark tone, you will not be able to see the contents of these images.

I should also say my interest is limited to planes that can be folded from a single sheet of paper. No cutting, no taping, no paper clips. Just the paper and folding. This is both a sanity-preserving creative constraint5 If there were no limits, I would go nuts trying to optimise my paper airplanes to the point where they may not even resemble paper airplanes anymore. and in order for the airplane to be somewhat safe in the hands of toddlers.

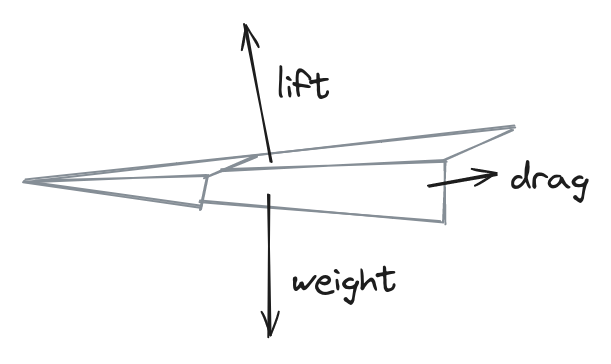

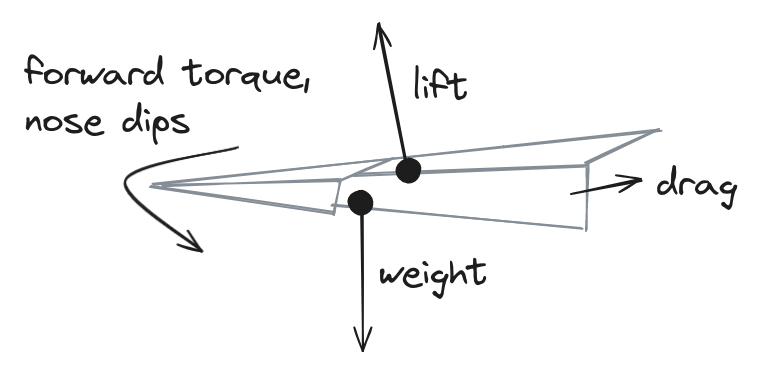

Paper planes have no propulsion, so on a macro level, in stable flight, they only experience three forces: drag, weight, and lift. We will look into these forces in more detail.

Figure 2: Paper airplane, forces in stable flight

Straight (non-turning) flight

We are going to focus on straight (non-turning) flight for two reasons:

- It makes things much simpler (as we will soon see), and

- In my experience, taking a straight-flying paper airplane and making it a turning airplane is much easier than going the other way around.

Fortunately for us, airplanes (paper and real ones) are usually designed to be symmetric. This symmetry guarantees that the forces generated on both sides of the airplane will be equal, and there is nothing that makes it turn.6 In a real airplane, the pilot has the responsibility of deforming the plane to break the symmetry when it needs to turn – this is the purpose of ailerons and rudder.

To get straight flight, we just need to be very careful to preserve symmetry when we fold our paper airplane. Easier said than done, but not a conceptual concern worth discussing further.

Angle of attack

Before we go into anything else, we need to understand angle of attack. If there is only one thing you understand about fixed-wing flight, it should be angle of attack.

In an early bible on airplane design7 Theory of Flight; von Mises; McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1945., von Mises says,

The flight path of the airplane can be controlled … through the control over the equilibrium angle of attack \(\alpha\), angle of sideslip \(\beta\), angle of bank \(\phi\), and output of the powerplant.

First off, we have a paper airplane so there is no powerplant providing output. Since it’s flying straight, we also don’t have an angle of sideslip. We might end up with an angle of bank (rolling motion) – but we’ll eliminate that shortly, so we can ignore that component also.

That means the flight path of our paper airplane can be controlled only through the equilibrium angle of attack \(\alpha\). That’s it. Once we have selected and folded a design, we have one parameter that determines the flight path of our airplane.

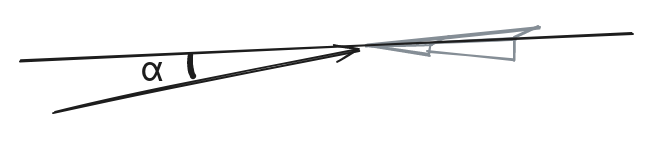

The angle of attack is the angle of a wing against the oncoming wind. A high angle of attack means the wing presents a larger surface area against the oncoming wind, which means it pushes more air out of the way, which means it produces more lift. A low angle of attack means the wing slices more cleanly through the air, and thus produces less lift.8 You can probably intuit this relationship: imagine sweeping your hand through water. If you hold your hand parallel to the arc of the sweep, it will not really want to go anywhere other than forward. If you angle it slightly against the sweep, it willl want to move up or down as more water pushes on its flat side.

Figure 3: Line is angle of wing, arrow is angle of oncoming air. The difference is angle of attack.

We often define zero angle of attack to be the angle that produces no lift. Then as angle of attack increases, the lift produced increases. At some point, increasing angle of attack further will start to reduce the lift produced – this is known as the stalling regime and it’s unstable so we want to avoid it. A wing in this region is known as stalled.9 Note that a stalled wing still may produce lift, it’s just that increasing angle of attack of a stalled wing further no longer means that it produces more lift, and an airplane is not designed to be stable under that condition.

We’ll leave it at that for now, but angle of attack is so important that we will come back to it multiple times later, and explore its consequences further.

Roll-stable (right-side-up) flight

Some paper airplanes roll over and fly upside down as soon as they are launched.

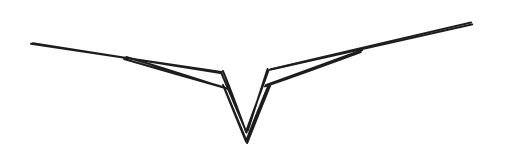

This can be fixed by making the wings dihedral. That strange Greek charm is fulfilled when you look at the paper airplane from behind, and the wings slope upwards a little as they go out from the keel. I.e. your paper airplane has dihedral when the wing tips are higher than the wing roots when seen from behind.10 Or from the front, I suppose. This is the stable configuration that prevents the paper plane from rolling upside down mid-flight.

Figure 4: Dihedral is when the wingtips are higher than the wing roots, here seen from behind.

The reason this works is that when an airplane with dihedral rolls over a little to one side, its lift vector will start pointing to the side, which initiates a side-slipping motion through the air, which means the oncoming air pushes on the top of the trailing wing harder than the nearest wing11 This is that angle of attack idea again, except now considering only the lateral component of the oncoming wind., which produces a counter-torque that rotates the plane back upright.

Lift and gravity

Gravity pulls the paper plane toward the ground. Lift is produced by the wings and pulls the plane toward the sky. For a well-designed paper airplane, these two forces have – to a first approximation – exactly the same magnitude but are pointed in opposite direction.

In other words, we can assume that lift nearly perfectly cancels out gravity. Intuitively, you might think this means a well-designed paper plane flies forever, but this is not the case. When lift cancels out gravity, the plane glides toward the ground at a constant speed.12 Recall Newton’s first and second laws: if the forces balance out to zero, an object will not experience acceleration, i.e. it will have a constant velocity. This is the key difference between an airplane and a ballistic projectile. A ballistic projectile accelerates toward the ground, whereas an airplane falls to the ground at nearly a constant speed.

Since lift balances out gravity, we actually know the magnitude of the lift force our paper airplane experiences: it’s the weight of the paper it is folded from! If we are folding a paper airplane out of A4 paper that has a paper thickness of 80 g/m², then the mass of the plane is 5 g, and the weight is approximately 0.05 N.

This means that any design we fold from that paper, however it looks, has wings that generate 0.05 N as long as it achieves stable flight.13 To a first approximation, still. The lift vector may be pointing slightly forward or back for angle-of-attack reasons, meaning the actual lift generated is slightly larger so that the component of it that is opposite to gravity balances the weight. Isn’t that crazy?

Pitch-torque balance

On the topic of lift and gravity, there’s one thing that often prevents stable flight. We know where the gravity acts: through the logically named centre of gravity. This is the balance point of the mass of an object.

There’s also a similar concept called the centre of lift: this is the balance point for where lift is generated. As long as the plane is symmetric, the centre of gravity and centre of lift will both be in the lateral centre of the paper airplane.

However, the centre of gravity can be behind the centre of lift, and then the plane will tend to pitch up in flight, because gravity tugs down at the back of the plane, while lift tugs up at the front. Similarly, if the centre of gravity is in front of the centre of lift, the plane will tend to pitch down.

Figure 5: Centre of gravity ahead of centre of lift creates a pitch-down torque.

This might seem like something that’s inherent to a paper airplane design and not something that can be adjusted after the fact, but it is not necessarily so. Think about it: if this balance was not possible to adjust on a real small airplane, then the plane would have to be designed for pilots of a specific weight, because a heavier pilot would shift the centre of gravity forward from the centre of lift and destabilise the airplane.

Real pilots can adjust this balance through the trim control. We don’t have one on our paper airplanes, but it’s an important enough concept that we will discuss it.

But! Under the right conditions, the airplane itself can also adjust this balance. We’ll learn how shortly.

Trim and angle of attack

All stable airplanes have a specific equilibrium angle of attack. This means they will, when left to their own devices, seek up and maintain a specific angle of attack. They do this by (with no input from the pilot) pitching forward or back until they are at the equilibrium angle of attack. If you want a good introduction to how that happens, I suggest reading chapter 6 of Dencker’s excellent See How It Flies.

In normal airplanes, the pilot can adjust this equilibrium angle of attack through the trim control, which changes the shape of the tail of the aircraft to give it a different equilibrium angle of attack. With paper airplanes, we have limited ability to adjust the trim of a folded design.

Additionally, the sort of paper planes we fold are generally tail-less. In broad strokes14 Broad strokes are necessary here because I don’t fully understand the details., what’s needed for a tail-less paper plane to be stable (i.e. have an equilibrium angle of attack) is a canard-like surface. A canard is a smaller forewing ahead of the main wing, that is mounted at a higher angle of attack than the main wing.

Some paper airplanes do have an explicit canard, like this design, for example.

Figure 6: Paper plane design with canards, the ear-looking protrusions at the front.

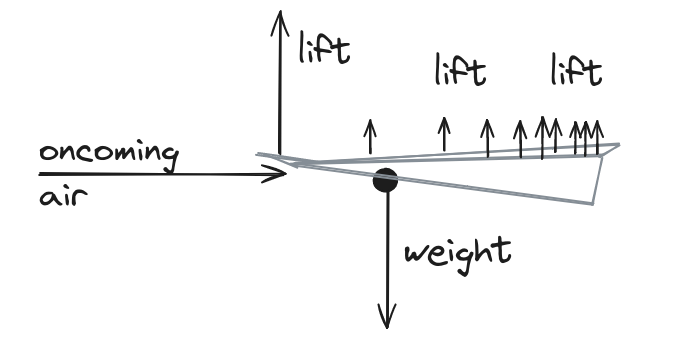

Note in the design above how the canard is folded slightly upwards, which means it has a higher angle of attack than the main wing. When this paper plane cruises in level flight15 Ignoring drag for a moment to keep things simpler. the canard produces more lift relative to its area than the main wing does. However, the main wing is larger. When all these forces are added together they end up resulting in the centre of lift, which is hopefully just about over the centre of gravity.

Figure 7: Higher angle of attack on the canard results in more lift there.

This difference in angle of attack between the canards and main wings is known as decalage.

Dynamic effect of decalage in flight

Once the airplane has positive decalage it will maintain its equilibrium angle of attack.

If the lift vector is too far forward, the airplane will pitch up and as that happens, the lift vector moves backward because the main wings’ lift generation increases more than the canards’. Similarly, if the lift vector is too far back, the airplane will pitch down and as that happens, the lift vector moves forward because the main wings’ lift generation decreases more than the canards’.

This means the positive-decalage airplane – on its own – finds the right pitch to balance the centre of lift with the centre of gravity. This is another important principle of paper airplane design: it must have positive decalage.

Trim in the absence of canards

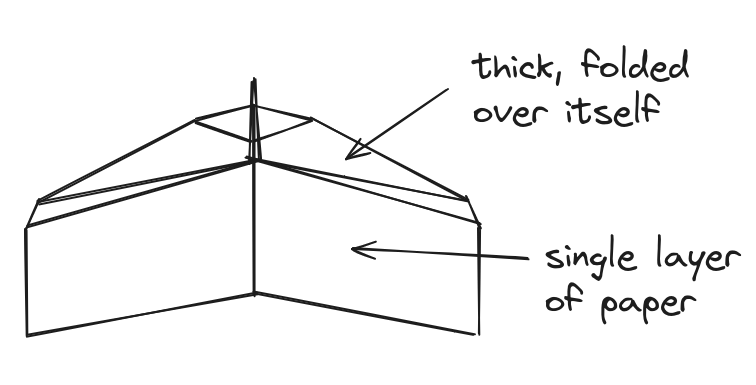

All of the above discussion referred to canards, but the requirement I initially stated required only a canard-like surface. Most paper plane designs do not have canards – however, they have something that acts like a canard.

They generally have a thicker leading edge on the wings. The trailing part of the wings generally consists of a single sheet of paper, whereas the leading edge is folded over itself at least one time. This fold is – not by accident – on the underside of the plane.16 The top side of paper planes is usually very smooth to encourage attached airflow, which improves circulation and thus lift. But I don’t know how big this effect is for paper planes, and that would be part of the performance article if I ever figure it out.

Figure 8: One of my favourite designs, here seen from underneath.

The illustration shows the underside of one of my favourite paper plane designs, and it’s clear that the front part of the wings has more layers of paper on it.

Angle of attack and airspeed

Next

- trim (pitch stability)

- drag

- speed

- lift

- drag is small compared to lift/weight