What Killed Perl?

Trick question! Perl is not dead. I’ll show you what I mean, and then still answer what I think killed Perl.

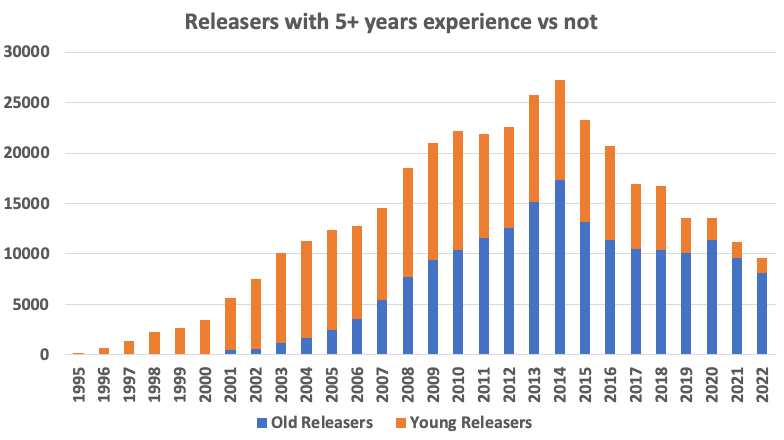

The cpan Report 2023 put together by Neil Bowers quite clearly illustrates that Perl’s popularity is somewhere in the same range it was during the dotcom bubble.1 I realise cpan usage isn’t a perfect proxy. There are probably a lot of people like me who use Perl specifically for things where they don’t need to interact with third-party libraries. These wouldn’t show up in the cpan records either, obviously. But it’s the best proxy I have. If anything, it’s higher: popularity increased ever so slightly after 2022, as next year’s cpan report will show. (Neil says he will publish it in January, so follow his blog for the latest news.) But it is also clear that newcomers make up a decreasing portion of the Perl crowd, and this has been the case since 2011. Why is that?

Some people seem to think Raku (formerly known as “Perl 6”) sucked momentum out of Perl, but I don’t believe that. Everyone I talked to back then knew Perl wasn’t going anywhere. Humanity had chained too much of the infrastructure of the growing internet to it. Even if Raku turned out to be a wild success, someone would have to keep maintaining Perl for many years to come. There was never any danger of obsolescence in starting a new project in Perl.

Besides, Raku was first announced in 2000, and the major burst of activity around Raku implementations seems to have been at the end of that decade. Through that period, Perl grew rapidly, as indicated by the graph.

I still struggle to understand why Perl went out of favour, which is understandable if you know what I think about it. But I have heard two reasons that resonate with me.

- The people who grew up on Unixy systems in the 1990s and early 2000s would know shell, C, awk, sed, Vim, etc. To these people, Perl is a natural extension of what they were already doing. Then in the 2000s came a new generation of programmers brought up on … I don’t know, Microsoft systems, Visual Basic and Java? These people were more attracted to something like Python as a second language, which then became popular enough to become the first language of the generation after that.

- Back when people learned Perl, you didn’t just go online and download development tools for a programming language on a whim. Binary package managers that chase down dependencies on their own weren’t a thing until the early 2000s, I think? And even then they didn’t have all that many packages. So even if, I don’t know, Oberon or Eiffel would be a better fit for someone in the 1990s, they might have opted to go with Perl anyway because that was what they had. These days, this is not as much of a problem anymore.2 You’ll find that the invention of many of the popular languages of today, such as Rust, Kotlin, Elixir, TypeScript, and Go happen to coincide with the growth of the internet and increased power of package managers.

So to state my hypothesis briefly: people today are both less predisposed to understand Perl, and have easy access to so many other alternatives. It’s a rather unsatisfactory explanation, but it’s the closest I can get.

Comments

: Higuita

My take on this:

- Regexes: While very powerful, new users have problems with it. They see it as random characters and have resistance to learn it. Perl code uses a lot of it, so it also scares away many new users. The younger they are, the more they look away from regexes. I think tools like sed and awk are great, but most younger people prefer to use other more complex tools (IDE, Excel) than to learn how to use those simpler tools to quickly parse or replace something.

- Code formatting: It is up to the user to use their own code standard. There is no right or common way to write Perl code. Everyone has their own small details and many have abused that, simply because it was good enough for them. This in turn makes code harder to read. In Python, the code formatting is required and will help a lot, especially for new users who are starting to learn.

- Write once, read never: The capability of Perl to do the same thing in multiple ways creates confusion. The use of implicit variables, optional formatting, and special variables makes it worse. This was abused in obfuscation contests, worsening the image that Perl is impossible to read after being written. Again, the regexes don’t help. They’re powerful, but not easy to read or understand. The more complex they get, the harder they are to read. While a good Perl program is easy to read, it does need comments to help people understand the flow. But then people forget to comment the code and the end result is that reading other people’s Perl code is usually slow.

- Easy to start learning Perl, hard to master: Every new Perl user that has tried to read obfuscated Perl code will feel that he or she will never reach the level required to read it. This can happen with any language, but Perl, being easy to obfuscate to just a few characters, excels in scaring people with how abstract it can become.

Perl 6: Since the language now known as Raku started being called Perl 6, it communicated that there would be a different Perl and this slowed down Perl 5 adoption. People weren’t sure how different it would be, so they would have to wait to see what would happen, and the image grew that Perl 5 was a dead ned. These things were enough problems to lose momentum and the advantage went to other languages. If Perl 5 kept going, or Perl 6 was Perl 5 with more features (or cleanup, to solve some of the problems Perl 5 had), it could have stayed alive for longer. Promoting a standard code style would have helped new users access the language.

Major changes are always hard. The transition from Python 2 to Python 3 took many years and still many programs are using Python 2. Most only really changed to Python 3 because several importand Linux distributions finally refused to ship Python 2 packages. This also killed a lot of the Python momentum.

- Quick and dirty: Let’s face it. Perl is great to solve a problem. While it is good, it also means that many Perl programs are just that: hacks to solve a problem, quick and dirty. But that quick and dirty code is still being used today in many places and people are afraid of touching it. Those aren’t the best examples to use when introducing Perl to people!